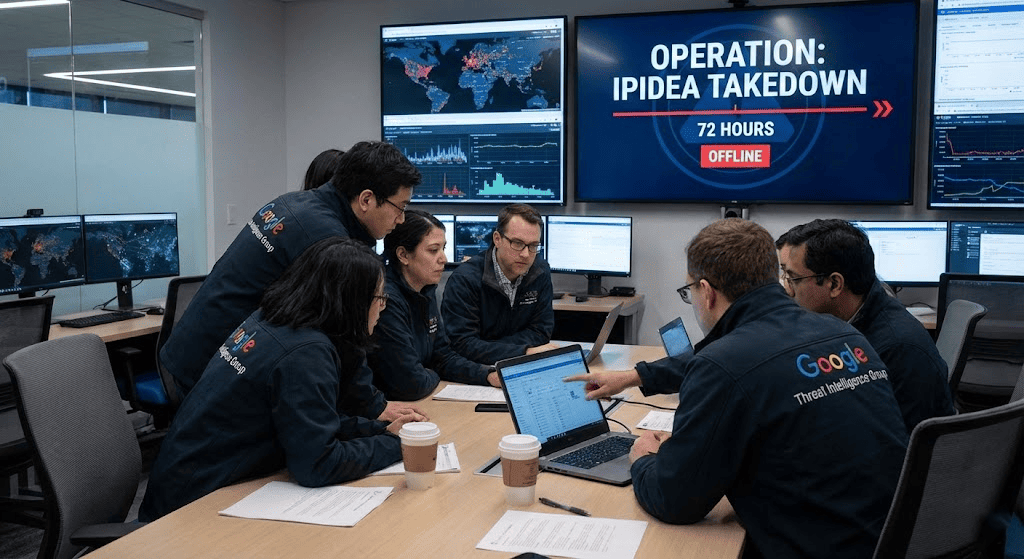

On January 29, 2026, Google's Threat Intelligence Group (GTIG) announced it had dismantled what it described as the largest residential proxy network on the planet. The target: IPIDEA, a China-based operation that had quietly enrolled millions of consumer devices into an infrastructure used by state-backed hackers, botnet operators, and organized cybercriminals across four continents.

Through coordinated legal action, domain seizures, and intelligence sharing with partners including Cloudflare, Spur, and Lumen's Black Lotus Labs, Google degraded IPIDEA's capacity by millions of exit nodes. IPIDEA's storefront at ipidea.io went dark. Its command-and-control domains were seized through a U.S. federal court order. Google Play Protect began automatically flagging and removing apps carrying IPIDEA's hidden SDK payloads.

What IPIDEA Actually Was

IPIDEA marketed itself as a premium residential proxy provider offering access to over 6.1 million daily updated IP addresses across 220+ regions. Behind that marketing, GTIG found something far more complex. IPIDEA wasn't a single service—it operated as an umbrella controlling at least a dozen ostensibly independent proxy and VPN brands, including 922 Proxy, 360 Proxy, Luna Proxy, ABC Proxy, Galleon VPN, and Radish VPN. As Sekoia's earlier research documented, the residential proxy market's apparent fragmentation is often an illusion. IPIDEA was a case study in that opacity.

The way IPIDEA built its IP pool was the core problem. Rather than sourcing IPs through transparent, consent-based agreements, IPIDEA distributed software development kits—Castar SDK, Earn SDK, Hex SDK, and Packet SDK—that developers could embed in their Android, Windows, iOS, and WebOS applications. Developers were paid per download. Once a user installed an app carrying one of these SDKs, their device was silently enrolled as an exit node in IPIDEA's proxy network. Google identified over 600 Android apps and more than 3,075 unique Windows executables connecting to IPIDEA's command infrastructure. Some Windows binaries masqueraded as system processes like OneDriveSync and Windows Update.

IPIDEA also operated free VPN apps—Galleon VPN, Radish VPN, Aman VPN—that provided real VPN functionality while simultaneously enrolling user devices as proxy endpoints. According to GTIG's analysis, many of these applications contained no meaningful disclosure that the user's device was being recruited into a commercial proxy network.

Inside the Two-Tier Architecture

GTIG's technical analysis revealed a centralized two-tier command-and-control system connecting all of IPIDEA's apparently separate brands through shared backend infrastructure.

Tier One operated through domain-based servers. When a device running an IPIDEA SDK started up, it connected to a Tier One domain, transmitted diagnostic information, and received a configuration payload containing a list of Tier Two nodes.

Tier Two consisted of approximately 7,400 IP-based servers distributed globally, including in the United States. Enrolled devices periodically polled these servers for proxy tasks, then established dedicated connections to relay traffic to whatever destination the proxy customer specified.

Despite the multiple brands, different SDK names, and distinct Tier One domains, GTIG confirmed that all SDKs shared the same pool of Tier Two servers. The number of Tier Two nodes changed daily, consistent with demand-based scaling—taking down individual Tier One domains would only temporarily disrupt connections while the shared Tier Two infrastructure continued operating.

That's what made the coordinated disruption critical. Google didn't target one brand or one set of domains. The legal action hit C2 infrastructure at both tiers simultaneously, while Cloudflare disrupted DNS resolution across the entire operation.

550+ Threat Groups in Seven Days

The scale of abuse was staggering. During a single seven-day period in January 2026, GTIG tracked over 550 distinct threat groups using IPIDEA exit nodes—spanning state-sponsored espionage from China, North Korea, Iran, and Russia, organized cybercrime syndicates, APT operators, and information operations campaigns.

GTIG Chief Analyst John Hultquist specifically noted residential proxies as a favored tool of Russian and Chinese cyber espionage, citing their use by APT28, Sandworm, and Volt Typhoon. Observed activities ranged from accessing victim SaaS environments to penetrating on-premises infrastructure to large-scale password spray attacks.

The botnet connections were equally alarming. IPIDEA's SDKs played a central role in the BadBox 2.0 botnet targeting cheap Android TV streaming boxes that shipped with proxy malware pre-installed. Google had filed a lawsuit against BadBox 2.0's operators in July 2025.

Then came Kimwolf. In late 2025, researcher Benjamin Brundage at Synthient discovered that Kimwolf botnet operators had found a critical vulnerability in IPIDEA's proxy infrastructure: the ability to tunnel through proxy connections and access local networks of enrolled devices. Because IPIDEA's proxy software didn't restrict access to internal network addresses, attackers could send crafted requests through the proxy to reach other devices on the same home network. Synthient tracked roughly 2 million compromised devices by late December 2025. Kimwolf was capable of launching DDoS attacks estimated at approximately 30 Tbps—and rebuilt itself from near zero to millions of infections in just days by exploiting IPIDEA's massive proxy pool.

Spur's research revealed residential proxies tied to IPIDEA inside nearly 300 government-owned networks, 318 utility companies, 166 healthcare organizations, and 141 banking and finance institutions—some belonging to the U.S. Department of Defense. Infoblox reported that nearly 25% of its enterprise customers had at least one device that connected to a Kimwolf-related domain since October 2025.

How Google Took It Down

The disruption was a coordinated multi-front operation.

Legal action: A U.S. federal court order enabled seizure of dozens of domains used for both C2 operations and marketing, simultaneously cutting IPIDEA's ability to manage enrolled devices and recruit new developers.

Platform enforcement: Google Play Protect was updated to detect IPIDEA SDK signatures, automatically warning users, removing affected apps, and blocking future installs. According to the Wall Street Journal, approximately nine million Android devices were removed from the network.

Intelligence sharing: GTIG shared technical intelligence about SDK signatures and C2 indicators with platform providers, law enforcement, and research firms. Cloudflare disrupted domain resolution. Lumen's Black Lotus Labs and Spur helped verify infrastructure scope.

Lumen confirmed a 40% decrease in total proxies compared to previous weeks. However, approximately 5 million distinct bots were still connecting to IPIDEA's C2 servers as of the announcement—a reminder that dismantling an operation of this scale is ongoing, not instantaneous. No arrests or indictments have been announced. IPIDEA's operators remain unidentified.

What This Means for Proxy Users

The IPIDEA takedown carries direct implications for anyone relying on residential proxies for legitimate work. The central lesson: sourcing transparency is no longer optional.

IPIDEA's pitch to developers was simple—embed our SDK, get paid per download. Many developers likely had no idea they were enrolling users into infrastructure exploited by state-backed hackers. Many proxy customers purchasing through IPIDEA's reseller network probably didn't know their traffic was routed through non-consenting devices. Because proxy operators frequently share device pools through reseller agreements, even well-intentioned providers can unknowingly sell access to compromised infrastructure.

For businesses that depend on residential proxies for competitive intelligence, ad verification, SEO monitoring, or pricing analysis, several evaluation criteria now matter more than ever. Ask how the provider sources its IP addresses—ethical providers obtain consent through transparent opt-in programs with clear disclosure. Look for providers that operate their own backend infrastructure rather than reselling from opaque upstream sources. A provider like Proxy001 maintains its own ethically sourced residential IP pool with transparent sourcing practices, giving users confidence their proxy connections aren't entangled in the kind of infrastructure that drew Google's enforcement action. Check for third-party security auditing, and consider the provider's transparency about its team, registration, and operational history.

The question for anyone choosing a residential proxy provider today isn't just "how many IPs do you have?" It's "where do those IPs come from, and can you prove it?"

Last updated: February 2026. Sources include Google Threat Intelligence Group's official blog, Synthient's Kimwolf research, Krebs on Security's investigative reporting, and analysis from Spur, Lumen's Black Lotus Labs, and SecurityWeek.

Start With a Provider You Can Trust

If the IPIDEA takedown reinforced one lesson, it's that proxy sourcing transparency matters as much as pool size or speed. Proxy001 offers ethically sourced residential proxy IPs with full opt-in consent, flexible rotation options for both static and dynamic use cases, and a global IP pool designed for legitimate business operations including market research, ad verification, and competitive analysis. With transparent infrastructure, responsive support, and no reliance on opaque SDK-based device enrollment, Proxy001 gives you residential proxy access without the compliance risks exposed by Google's enforcement action. Try it today at proxy001.com.